Written and Cartographic Accounts of Amizmiz in History

Amizmiz has been a part of recorded history for several centuries.

Travel accounts of European visitors to Morocco during the past 500

years nearly always include passages detailing their time passing

through Amizmiz. In the nineteenth century, this was especially true

of British explorers stopping at Amizmiz en route to the Atlas

Mountains. Before modern roads, the town was an important stop for

those hoping to cross the mountain range.

Like other Moroccan cities and towns, however, Amizmiz has been known

by a few different names over time.

Variations in the spelling of Amizmiz include all of the following:

Imizmizi, Imizimiz, Imizmiza, Imizmiz, Imisimis, Imismis, Amsmis, Amsmiz,

Amismiz, Amezmiz. There is no

doubt, however, that in each case the writer or mapmaker was referring

to modern-day Amizmiz.

Leo Africanus

Leo Africanus

(1494 - 1554) wrote the first detailed descriptions of Morocco ever published in Europe.

His work, entitled Description of Africa, was published in

1550 in Venice, with an English translation appearing in 1600. His

work includes passages on many cities in Morocco, only some of which

are still in existence today. Among them is his description of a town

called “Imizmizi,” what is now modern Amizmiz.

“Upon a certain part of

the Atlas stands a city called Imizmizi...and this

city the ancients are reported to have built. Near unto this city lies

the common highway to Guzula over the mountains of Atlas....snow falls

often thereupon...Not far from this town likewise there is a very fair

and large plain, which extends for the space of thirty miles, even to

the territory of Maroco (Marrakech). This most fertile plain yields

such excellent grain, as (to my remembrance) I never saw the like, and

the flour is perfect. Because the Arabians and soldiers of Maroco do

so much molest this plain country, the greater part thereof is

destitute of inhabitants. Indeed, I have heard of many citizens that

have forsaken the city itself, thinking it better to depart, than to

be daily oppressed with so many inconveniences. They have very little

money, but the scarcity thereof is recompensed by their abundance of

good ground, and their plenty of grain.”

“Upon a certain part of

the Atlas stands a city called Imizmizi...and this

city the ancients are reported to have built. Near unto this city lies

the common highway to Guzula over the mountains of Atlas....snow falls

often thereupon...Not far from this town likewise there is a very fair

and large plain, which extends for the space of thirty miles, even to

the territory of Maroco (Marrakech). This most fertile plain yields

such excellent grain, as (to my remembrance) I never saw the like, and

the flour is perfect. Because the Arabians and soldiers of Maroco do

so much molest this plain country, the greater part thereof is

destitute of inhabitants. Indeed, I have heard of many citizens that

have forsaken the city itself, thinking it better to depart, than to

be daily oppressed with so many inconveniences. They have very little

money, but the scarcity thereof is recompensed by their abundance of

good ground, and their plenty of grain.”

Luis del Mármol Carvajal

Luis del Mármol Carvajal (1520 - 1600) wrote another 16th century account of Africa entitled General Description of Africa, first published in a Spanish edition in 1573. In chapter 38 of Book III, Carvajal includes a section on “Imizimiz,” most of which is a direct translation from Leo Africanus. There is an interesting note of optimism at the end, however. While Leo had commented that much of the Amizmiz area was losing inhabitants due to outside incursions, Carvajal ends his account by stating, “Now it is very populous, and the inhabitants have been well treated because of an Almoravid called Sidi Canon, who was from it.”

Maps of Abraham Ortelius

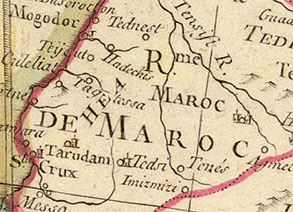

Besides the inclusion of Amizmiz in various written historical

accounts, another indication of its importance can be found in the

many maps of Morocco that include it as well. The earliest and most

important of these is the 1570 atlas of Abraham Ortelius entitled

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. This is generally regarded as the first

modern atlas, comprised of 53 maps covering the known world of the

time. His map of “Barbariae,” or the Barbary Coast, charts the modern

nations of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The major city of “Marocho”

(Marrakech) is included on the map, as is the smaller town of “Imizinizi.”

This spelling is no doubt a copying error of what was probably

intended to be “Imizmizi,” the name given by Leo Africanus. However,

the second “m” was miscopied as the letters “in.” By his 1595 edition

map of Morocco, this error had been corrected.

Besides the inclusion of Amizmiz in various written historical

accounts, another indication of its importance can be found in the

many maps of Morocco that include it as well. The earliest and most

important of these is the 1570 atlas of Abraham Ortelius entitled

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. This is generally regarded as the first

modern atlas, comprised of 53 maps covering the known world of the

time. His map of “Barbariae,” or the Barbary Coast, charts the modern

nations of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The major city of “Marocho”

(Marrakech) is included on the map, as is the smaller town of “Imizinizi.”

This spelling is no doubt a copying error of what was probably

intended to be “Imizmizi,” the name given by Leo Africanus. However,

the second “m” was miscopied as the letters “in.” By his 1595 edition

map of Morocco, this error had been corrected.

Below is a detailed section of the 1570 map of the Barbary Coast,

showing both “Imizinizi” and “Marocho”:

In 1595, Ortelius produced a map of Morocco that included

corrections from his 1570 map. Here, we see Amizmiz now written as “Imismis.” The

great city of “MARRVECOS” (Marrakech) is also visible:

Map of Nicolas Sanson

One of the major reasons that Amizmiz held importance for European

explorers in the 16th to 19th centuries was due to the fact that it

was an important stop before crossing what are now known as the High

Atlas mountains. Leo Africanus mentions this fact in his description

of Amizmiz, but we also encounter evidence of it from a 1655 map by

Frenchman Nicolas Sanson. His map of Morocco clearly places “Imizmiza”

next to a route passing over the mountains into the region of “Guzula.”

The city of “Marochvm” (Marrakech) is also visible:

English Map of S. Bulton

The English map of S. Bulton from 1800 places “Imizmizi” barely

within the “Kingdom of Maroco,” an indicator that the town would have

been one of the last stops still under the control of the Sultan

before entering the mountains:

The British Explorations of the 19th Century

The 19th century saw an increase of British interest in Morocco and

its geography. The 1809 publication of An Account of the Empire of

Marocco by James Grey Jackson marked one of the earliest

firsthand accounts by someone who had spent a considerable amount of

time in the country. Jackson recognized the scarcity of reliable

information about Morocco, and suggested that “Leo Africanus is, with

very few exceptions, perhaps the only author who has depicted the

country in its true light” (11).

The first volume of The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society,

published 1831, contains an account of Lieutenant Washington's

expedition to Morocco in the winter of 1829-1830. He travelled south

of Marrakech into the Atlas mountains, but stayed northeast of Amizmiz

and therefore does not mention the town. However, it is interesting to

note what he does say about the Atlas mountain region and its people:

“How little is known of the central recesses of the Atlas! Doubtless

these valleys are all inhabited by a race of men probably as unmixed

as any existing, of whom nothing is known, hardly even a few words of

their language! Here is a field for an inquiring mind” (149).

Throughout the century, many explorers took up that challenge. In

fact, the exploration of the Atlas mountains was one of the major

recurring projects by members of the Royal Geographical Society during

its first seven decades of existence. In almost every instance,

Amizmiz was included in the itinerary of British explorers surveying

the people, plant life, and geography of the Atlas mountains.

1836 - John Davidson

In August of 1835, world traveller John Davidson embarked on a

journey that he had hoped would take him all the way to Timbuktu.

Unfortunately, he was killed approximately 25 days before reaching the

city. However, his account of travels in Morocco is filled with

stories of personal encounters with Arab and Berber Moroccans.

Published posthumously in 1839 by his brother under the title Notes Taken

during Travels in Africa, Davidson's journal includes entries

from February 21-23, 1836 that speak of the town of “Almishmish,”

which his brother interprets as “Imizmizi” in a footnote entry. The

entries are below:

Sunday, Feb. 21.—Therm. 47°

Our road was very beautiful, but trying, as we continued to ascend.

Some of the ravines surpass any thing I have ever seen. We passed

several tanks, built along the route, for the convenience of

travellers: the water was fine: I picked up many curious specimens. At

three P.M. we crossed the river Nefísah, a noble stream; above which

stands the town of El-Arján, where we saw the women's heads dressed

fantastically with flowers, and some fakirs adorned with curious

ornaments. We did not reach Almishmish [Amizmiz] till just before

dark. The Sheïkh Sídí Mohamed Ben Aḥmed is a great Káïd, who sent us

lots of presents. This, which I hoped would be an easy day, turned out

the hardest of any we had travelled. My horse is so knocked up, that I

find we must remain here the whole of to-morrow.

Monday, Feb. 22.—Therm. 50°

There was a little rain during the night. I have been so bitten by

fleas, that I look like a person with the small-pox. Our journey

yesterday was twenty miles, W. by S. and W. S.W.; we went a part of

the way up the dry bed of a river. I found here some varieties of

mixed stones, and a spring nearly equal to that at Vaucluse: there

were numerous mills scattered through the country, which was very

beautiful. We went to breakfast with the Káïd in his garden; it was

done in great style. Received lots of presents, and had many patients,

especially some old women; amongst the rest, there was brought to me a

man who had been attacked when employed in the fields, and had both of

his arms broken and half of his nose cut off: I replaced the piece of

the latter and set the arms, for which I had to manufacture

splints....Many of the ladies here are ill, but I have no remedy for

them. The chief of the Jews sent for me, to shew his hospitality; but

I have no appetite....I must, however, pay him and his household a

visit....Long—very long, will it be before I forget this

visit....Returned home about eleven, P.M.; it was very cold.

Tuesday, Feb. 23.—Therm. 50°

It turned very cold. I remarked on the road the strange manner of

keeping their corn in large baskets, plastered over, and set on the

roofs of the house, where they present a very odd appearance. Received

presents again before starting, which did not take place till nine,

A.M.

1839 - Royal Geographical Society

The ninth volume of the Journal of the Royal Geographical

Society mentions Davidson's earlier exploration of Morocco, and

specifically mentions the route he takes past Amizmiz. This no doubt

contributed to making Amizmiz a regular stop for later British

explorers. The relevant passage is reproduced here:

“In Marocco we find, from the rough note-book of the lamented

Davidson, that, following the steps of the British mission to that

country in 1830, related in the 1st Vol. of the Geographical Journal,

he proceeded from the city of Marocco across the plain in a S.S.E.

direction into Atlas, as far as the ruined town of Tasremút, at an

elevation of 3000 feet above the sea; thence turning to the westward

he continued along the valleys of Atlas by a route not laid down in

any of our maps, and which we are enabled partially to trace only in

that of M. de Gråberg; passing within a few miles of the site of

Aghmát Warikah, he appears to have issued from the mountains beyond a

place called Amishmish, perhaps Imizmizi of our maps, and then to have

crossed the plain to Mogador. Geographers cannot but feel grateful to

Mr. Thomas Davidson, the traveller's brother, for allowing his rough

notes of this novel route to be made public” (lxxii - lxxiii).

1871 - Joseph Hooker

A close friend of Charles Darwin, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was one

of Britain's greatest botanists and explorers of the 19th century. For

two decades he was the director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew,

during which time he made a visit to Morocco in 1871 in order to

collect specimens of plant and animal life. His account of

that journey, written with John Ball, was entitled Journal of a

Tour in Marocco and the Great Atlas (1878). That account contains

the most detailed description of “Amsmiz” up until that time period.

Hooker spends considerable length detailing the geography, plant life,

and notable people of Amizmiz and the Amizmiz valley. In fact, it is

through the Amizmiz valley that Hooker and Ball ascend the Atlas

mountains to the peak known at that time as Djebel Tezah, from which

the two view the Sous valley before returning back to Amizmiz. From

the vast amount of material, here are some notable passages:

A close friend of Charles Darwin, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was one

of Britain's greatest botanists and explorers of the 19th century. For

two decades he was the director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew,

during which time he made a visit to Morocco in 1871 in order to

collect specimens of plant and animal life. His account of

that journey, written with John Ball, was entitled Journal of a

Tour in Marocco and the Great Atlas (1878). That account contains

the most detailed description of “Amsmiz” up until that time period.

Hooker spends considerable length detailing the geography, plant life,

and notable people of Amizmiz and the Amizmiz valley. In fact, it is

through the Amizmiz valley that Hooker and Ball ascend the Atlas

mountains to the peak known at that time as Djebel Tezah, from which

the two view the Sous valley before returning back to Amizmiz. From

the vast amount of material, here are some notable passages:

“This [Amizmiz] is the most considerable place on the northern

declivity of the Great Atlas, and, from the number of inhabitants, may

deserve to rank as a town. It stands on a shelf of flat rocky ground,

somewhat above the level of the adjoining plain, and nearly 200 feet

above the stream issuing from the mountains close at hand, which, for

want of any other name, we have called the Amsmiz torrent” (246).

“The Governor [of Amizmiz] was courteous and even friendly in manner,

and in general terms expressed his readiness to forward the objects of

our journey. He seemed pleased with the articles which Hooker

presented to him— a musical box, an opera-glass, and a long

sheath-knife; but when a thermometer was added, and an attempt made to

explain the use of the instrument, he at once returned it, saying that

it would be of no service, and that he would much prefer a brace of

pistols” (248).

“In the afternoon we went out for a stroll, and were able to form a

better idea than we had hitherto done of the character of the scenery.

The position of Amsmiz somewhat reminds one of that of villages in

Piedmont, that stand at the opening of some of the interior valleys of

the Alps, and still more of similar places in the Apennines of Central

and Southern Italy. The lofty hills that form the outer extremity of

the spurs diverging from the Great Atlas slope rather steeply towards

the plain, while the torrent issues from them through a cleft so

narrow that no path is carried along it into the valley. Trees, that

naturally clothe the outer ranges of the Alps, are here very scarce,

and the upper declivity, as commonly in the Apennine, is covered with

brushwood and low shrubs; while the lower slopes are partly under

tillage, or else planted with olive and fig trees. We descended from

the plateau, where our camp stood close to the town of Amsmiz at 3,382

feet (1,030.7 m.) above the sea, by steeply sloping banks to the level

of the torrent; and followed this for some distance, collecting plants

by the way; and then made a circuit among fields, enclosed by high

hedges, in which grew a profusion of climbing plants. The chief prize

of our excursion was a curious new species of Marrubium,

whose spherical heads of flowers are beset with long stiff bristles

hooked at the end, formed by the elongated lower teeth of the calyx”

(249).

1887 - Walter Harris

A fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Walter B. Harris was a member of an official

1887 diplomatic mission to the Sultan of Morocco in Marrakech (depicted at right).

In his book The Land of an African Sultan, published 1889,

Harris details his time in Marrakech and and also some of the travels

that were taken by members of the diplomatic mission.

Four of those members, Harris included, were given special permission

by the sultan, Moulay Hassan, to visit the Atlas mountains in May of

1887. They were provided an interpreter, four soldiers, some servants,

and a letter from the sultan himself: “We give permission, by the help

of God, to the four Englishmen who are bearers of this letter to

travel in all parts of our Empire in which there is no present danger.

But in parts where there is danger, or where the inhabitants are in

rebellion, they must not go, whether in the plains or mountains. And

to those whose business it is, I give this command...that they take

care of them and pay all attention to their wants; that they accompany

them, and supply a fitting escort; and that they point out to them the

dangerous places, and advise them not to enter them. --Moulay Hassan”

In their journey, the Englishmen visit Ourika, Asni, and eventually

Amizmiz. Harris noted that “Amsmiz is a place of some size and

importance, and boasts a 'mellah,' or Jews' quarter, separated from

the walled town, of which latter the mosques and gateway are fine.

Altogether it is a most picturesque place, situated in the opening of

a large valley” (238).

Over the course of several days in Amizmiz, the

group explores that valley and some of the mountain villages near

Amizmiz: “Early next morning we started off up the valley, keeping to

the right-hand side. The path, the merest track in the side of the

precipice, was not a good one, as it was in no place more than two

feet to three feet wide, and proportionately slippery. Riding along

such roads as these is not over-pleasant work, especially when,

hundreds of feet below one, rushes a turbulent river, into which one

would ultimately alight...should the horse make one false step.

However, after some two hours and a half of more or less holding one's

breath, we emerged into a valley running at right angles to the one we

were in. The scenery all along the road was very grand; far below

boiled and bubbled the river, its banks green, vividly green, with

narrow strips of corn-fields and groves of walnut-trees, while a line

of crimson oleanders marked out the river's edge. The valley we

entered was very lovely. At the end, which opens into the great

valley, stands a village of some size, by name Imminteli, close under

the walls of which runs a swift, clear, deep river, whose bed is cut

out in the solid rock. On each side of the river is a lawn of green

grass, the whole shaded by gigantic walnut-trees. We crossed the river

some few hundred yards up to where it issues from the solid rock, a

most curious spot, for there is no cave, simply a pool of water at the

foot of the precipice—a clear, deep pool, from the centre of which,

far down in its transparent depths, issues the stream” (240-241). The

Amizmiz

valley, the village of Imintala [Imminteli], the famous spring that flows

into a river surrounded by grass and walnut trees—all of these can still be visited today (see our villages

map and our custom excursion itinerary).

1888 - Joseph Thomson

A Scottish geologist and explorer, Joseph Thomson was famous for his

travels throughout Africa. A fellow of the Royal Geographical Society,

Thomson made a trip to the Atlas mountains in 1888. A year later he

published a personal narrative of that trip entitled Travels in

the Atlas and Southern Morocco: A Narrative of Exploration. In

it, he describes the geography and

people of Amizmiz and the river valley to the south. He is

also the first person (that we know of) to ever photograph Amizmiz.

A Scottish geologist and explorer, Joseph Thomson was famous for his

travels throughout Africa. A fellow of the Royal Geographical Society,

Thomson made a trip to the Atlas mountains in 1888. A year later he

published a personal narrative of that trip entitled Travels in

the Atlas and Southern Morocco: A Narrative of Exploration. In

it, he describes the geography and

people of Amizmiz and the river valley to the south. He is

also the first person (that we know of) to ever photograph Amizmiz.

Thomson begins his description of Amizmiz with a general survey of the

geography: “Amsmiz lies at the foot of the outer mountain terrace of

the Atlas, and close to the entrance of a narrow glen, through which

may be caught a glimpse of the backbone of the range, only some eight

miles distant. The town stands at an elevation of 3020 feet above the

level of the sea, according to our boilingpoint thermometer” (282).

He speaks of the people as well, including the sizeable number of

Jewish residents.

“The population of the town of Amsmiz we guessed to be somewhere about

2000, of which a very considerable proportion are Jews” (283). He

comments that the Jews of Amizmiz

“had a manly and independent air about them sufficiently rare in these

lands, and seemed to be on very good terms with themselves and with

the government” (283). Regarding all the inhabitants of the town,

Thomson remarks that they are a population of

“fine healthy men and women” (284).

Much more time is spent by Thomson describing the river valley and

mountains to the south. In fact, chapter 20 of his book is titled “Glen of the Wad Amsmiz,”

the word “wad” being Arabic for river. The entire chapter recounts

Thomson's exploration of the Amizmiz river valley, the same valley

that our excursions visit nowadays (see our maps).

Thomson remarks on the incredible beauty of the area:

“It had never before been our good luck to find such a charming

camping-ground. In the Atlas flat pieces of ground covered with green

sward and sheltering trees are extreme rarities; but here, in the glen

of the Wad Amsmiz, we had a delightful bit of turf on which to pitch

our tents, splendid walnut trees to shade them, a noisy torrent to

babble at our feet, and majestic mountains to fold us in their giant

arms and cool the tropic heats. Berber villages also were at hand, to

send us store of corn for mules and horses, milk, eggs, and fowls for

ourselves, and couscous, tajine, and barley bannocks for our attendants”

(290-291).

1897 - R. B. Cunninghame Graham

Bontine Cunninghame Graham was a Scottish adventurer and writer who

also spent several years involved in politics. In 1897, he travelled

to Morocco with the hopes of reaching the southern city of Taroudant

in the Sous valley, an area that had not been reached by earlier

explorers. Graham disguised himself as a Turkish doctor in order to

avoid the obstacles that often troubled Europeans who openly travelled

in Morocco. Despite his efforts, he failed to reach Taroudant when he

was imprisoned for four months by Berbers in the Atlas mountains. His

1898 book about his time in Morocco, entitled Mogreb-el-Acksa: a

journey in Morocco, contains numerous references to Amizmiz.

Bontine Cunninghame Graham was a Scottish adventurer and writer who

also spent several years involved in politics. In 1897, he travelled

to Morocco with the hopes of reaching the southern city of Taroudant

in the Sous valley, an area that had not been reached by earlier

explorers. Graham disguised himself as a Turkish doctor in order to

avoid the obstacles that often troubled Europeans who openly travelled

in Morocco. Despite his efforts, he failed to reach Taroudant when he

was imprisoned for four months by Berbers in the Atlas mountains. His

1898 book about his time in Morocco, entitled Mogreb-el-Acksa: a

journey in Morocco, contains numerous references to Amizmiz.

Originally, Graham had no intention of passing through Amizmiz. After

having arrived in Mogador (modern day Essaouira), three routes were

available for reaching Taroudant. Graham's first choice was to travel

along the coast to Agadir and then eastward. This was the preferred

course simply because he would not need to traverse the Atlas

mountains. Unfortunately, the local Howara tribe that controlled the

road from Agadir to Taroudant was in rebellion, and the road was

reportedly closed. Graham had two other routes available, both of

which required his passing over the Atlas mountains. Of the two, he

first chose the road leading from the town of Imintanout south across

the mountain range. He encountered another set of unfortunate events

upon his arrival in Imintanout, however. The tribe of Beni Sira closed

the pass because they were unhappy with the newly appointed governor,

and in recent days they had been opening fire on anyone trying to

cross the Atlas through their territory. Graham had only one other

route available to him if he wanted to get over the Atlas and reach

Taroudant: take the upper and more difficult pass to the Sous valley.

This route began in Amizmiz.

When Graham first arrives in Amizmiz, he describes a bit of what he sees.

“We crossed the Wad el Kehra, and early in the afternoon tied up our

animals under a fig-tree, with a river running hard by, a stubble field in

front, and Amsmiz itself crowning a hill upon our right. Amongst the ‘algarrobas,’ fig-trees and poplars, swallows flit, having come south, or

perhaps migrated north from some more southern land. At the entrance of the town stood the palace of the Kaid, an enormous structure made of mud and

painted light rose-pink, but all in ruins, the crenellated walls a heap of

rubbish, the machicolated towers blown up with gunpowder. The Kaid, it

seems, oppressed the people of the town and district beyond the powers of

even Arabs and Berbers to endure; so they rebelled, and to the number of

twelve thousand besieged the place, took it by storm, and tore it all to

pieces to search for money in the walls” (109).

“An orange grove, backed by a cane-brake, with the canes fluttering like flags, was near to us; cows, goats, and camels roamed about the outskirts of the town, as in Arcadia—that is, of course, the Arcadia of our dreams—or of Theocritus.”

“Jews went and came, saluting every one, and being answered: "May Allah let you finish out your miserable life"; but yet as pleased as if they had been blessed. Their daughters came, like Rebecca, to the well—all carrying jars—unveiled, and yet secure, for in this land few Moors cast eyes upon the daughter of a Jew.”

“Upon the ramparts, shadowy white-robed figures, with long guns, go to and fro, guarding the town from hypothetic enemies....On every hedge are blackberries and travellers' joy; whilst a large honeysuckle, in full flower, smells better than all Bucklersbury in simple time; a jay's harsh cry sounds like the howl of a coyote, and Europe seems a million miles away. In the evening light, the footpaths, which cut every hill, shine out as they had all been painted by some clever artist, who had diluted violet with gold” (111).

The Early Twentieth Century

The turn of the century brought with it a diminished interest in Amizmiz among British explorers and scientists. Much of the geography and flora of the Amizmiz valley had by now been documented and there was less need for using Amizmiz as a base for further exploration of the Atlas mountains. Nevertheless Amizmiz continued to be a popular cultural destination for those foreigners travelling in Morocco—especially because of its close proximity to Marrakech. Photographers, too, recognized Amizmiz as an easily accessible location for documenting, in print, the life of Berbers in the Atlas mountains. In the early twentieth century, Amizmiz would continue being mentioned regularly among written travel accounts of the country.

The Pall Mall Magazine - 1900

Writer F. G. Aflalo contributed a piece on “Morocco, the Imperial

City” to the British literary magazine

The Pall Mall in its January 1900 issue. Including photographs taken by the author himself, Aflalo

describes Marrakech (also known at the time as Morocco City) from a

purely literary, outsider's perspective. His account includes a

mention of “Amsmiz,” which he visited en route to the Atlas mountains

where he intended to search for a famous type of wild sheep in the

area:

“Away to the south-west [of Marrakech], just as the great [Atlas] range lifts itself above the burning plain, lies Amsmiz, the city of almonds, nestling amid its groves of perfume and colour, and showing on its battered barbicans traces of political differences with the dynasty, or with some robber tribe from the hills. History is not my theme, and I care not which. But the remains of the struggle are picturesque” (58).

Eugène Aubin - 1902

A Frenchman and world traveller, Eugène Aubin visited Morocco in

late 1902, a fortunate time when relations between the Sultan and

Europe “had, for the first time, opened up in some degree this

country, so hostile to foreign influences” (vii). An English account

of his travels was published in 1906 under the title Morocco of

To-day. Among his many descriptions of the country, Aubin speaks of Amizmiz:

“Amsmiz is a little town that nestles at the very foot of the range,

on the banks of a tributary of the river Nefis, whose ravine has a

setting of snowy summits. The earth dwellings, crowned by a square

minaret, huddle together on a piece of rising ground, dominated by the

ancient Kasbah of the Kaïd of the tribe. To-day the Kasbah is only a

heap of ruins. It was destroyed at the time of the death of the Sultan

Moulay el-Hassan, when the tribes of Southern Morocco, taking

advantage, as their custom is, of this unique opportunity of shaking

off the yoke of authority, rose in revolt against their Kaïds, and

pillaged the Jews. The revolt spread till it was almost universal, and

it was only the most powerful of the chiefs that were spared. The Kaïd

el-Masmazi has thought it wiser not to rebuild the ruined Kasbah. He

has removed his residence to a spot outside the city, in an azib

with fortified walls. Like all the other Kaïds, he is elsewhere, and

in his absence his son, Si Mohammed ould el-Hassan, rules the tribe in

the capacity of Khalifa” (43).

Copyright © 2020 Berber Travel Adventures